THE FOOL’S JOURNEY | QUARANTA | SPRING MAPS | THE LOS ANGELES SERIES | LOST PATTERNS | MERCURY | UNTITLED SERIES | LANDSCAPES | FLOWERS, ALWAYS

“The organic contours of geological borders are at odds with the clunky, arbitrary nature of state and national borders, revealing the latter as illusions in the same way as such borders are equally irrelevant to the virus.”

Susan Lizotte: Maps of an Uncertain Spring

Humans make maps to codify what we discover about the world, and to chronicle how we figure it out. As knowledge accumulates, cartographies shift, contours expand and elongate, borders are created and blurred and redrawn, horizons are surpassed, oceans crossed, and mountains measured. The unknown evolves in fits and starts toward an elusive total understanding. But how do we map an invisible terrain? How do we overlay what we see of the world with what we sense of it in our souls?

Lizotte’s Spring Map paintings have been directly inspired by the pandemic and its prolonged quarantine. Returning to years of earlier research into 14th century history and visual culture, Lizotte’s collation of the Covid-19 experience with the Plague of the Black Death begins, perfectly, with their maps. The series keystone work, Mappa Mundi, takes inspiration from Martin Waldseemuller’s 1507 map of the globe — a masterwork made at a time when the urge to explore a planet still all but unknown to Europeans really caught fire, and the first known map to name America. As Europeans spread out across the globe and celebrated their “discoveries,” they also acted as a veritable army of disease vectors, ironically bringing death with them everywhere in their quest to shine a light.

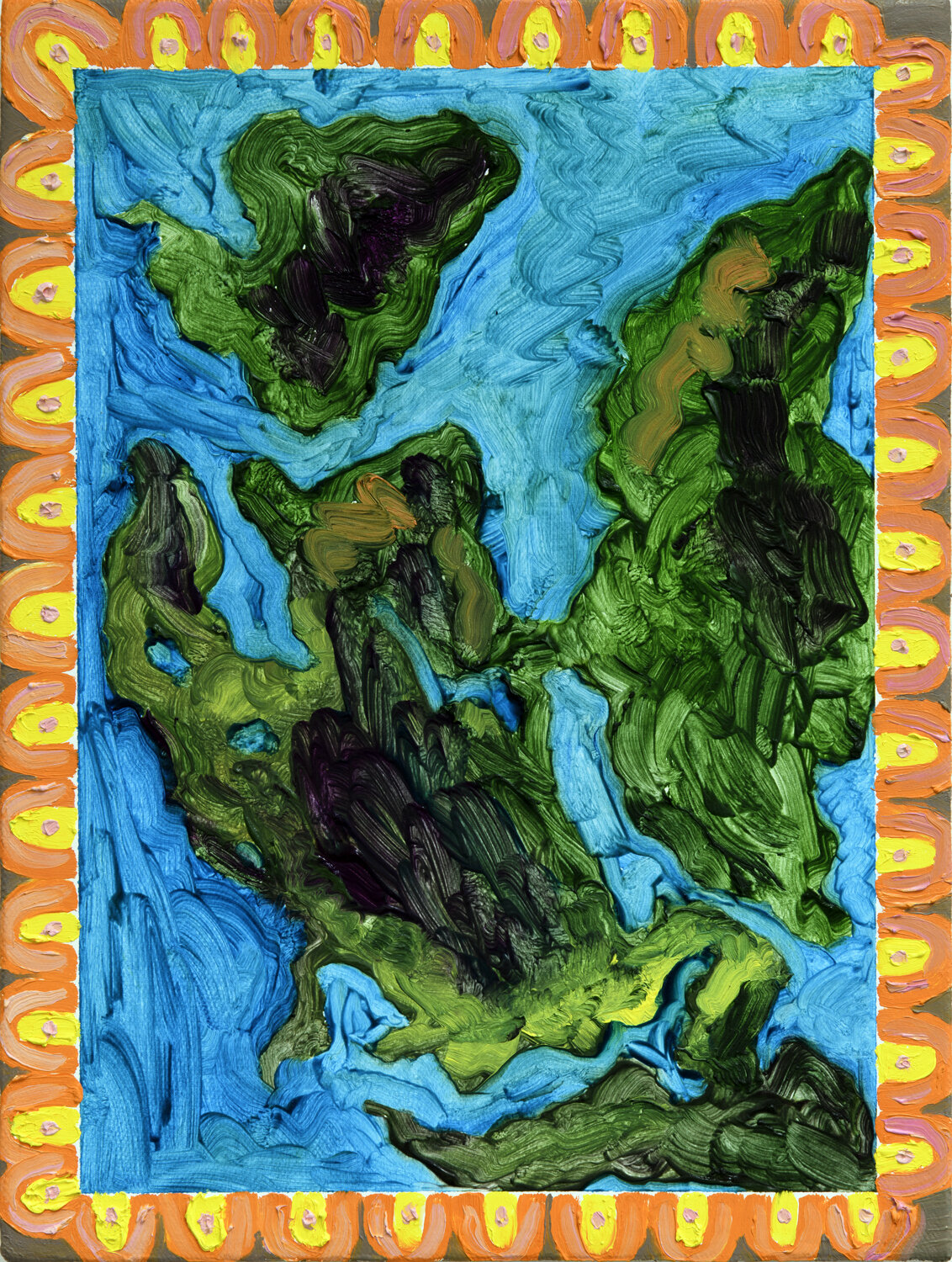

Building her version of this iconic map from a grid of 12 canvases serves to underscore the present day condition of lockdown, separation, isolation, and mistrust — neighbor from neighbor, nation from nation. At the same time, across the entire series actually, her use of old-time materials and mediums like sheepskin parchment, thick oil paint, walnut ink in fountain pens, and hematite crayon serve to tether the narrative to para-Columbian geopolitical events. The dynamic of authenticity and experimentation animates the entire portfolio with a liminal, non-linear strangeness that speaks to the distance between what we knew about the world back then and what we have since come to learn, and perhaps already forgotten.

Much as a Spring of uncertainty and lockdown gave way to a Summer of dismay and frustration, and on the cusp of an Autumn and Winter of madness and discontent, with perhaps a distant new Spring almost in reach, the explorers and map-makers pressed forward into absolutely unknown regions. Their first impressions often proved inaccurate, and look bizarre to us now, like distortions or outright inventions, or stormy places marked “here be dragons.” In other words, they look like how we currently feel.

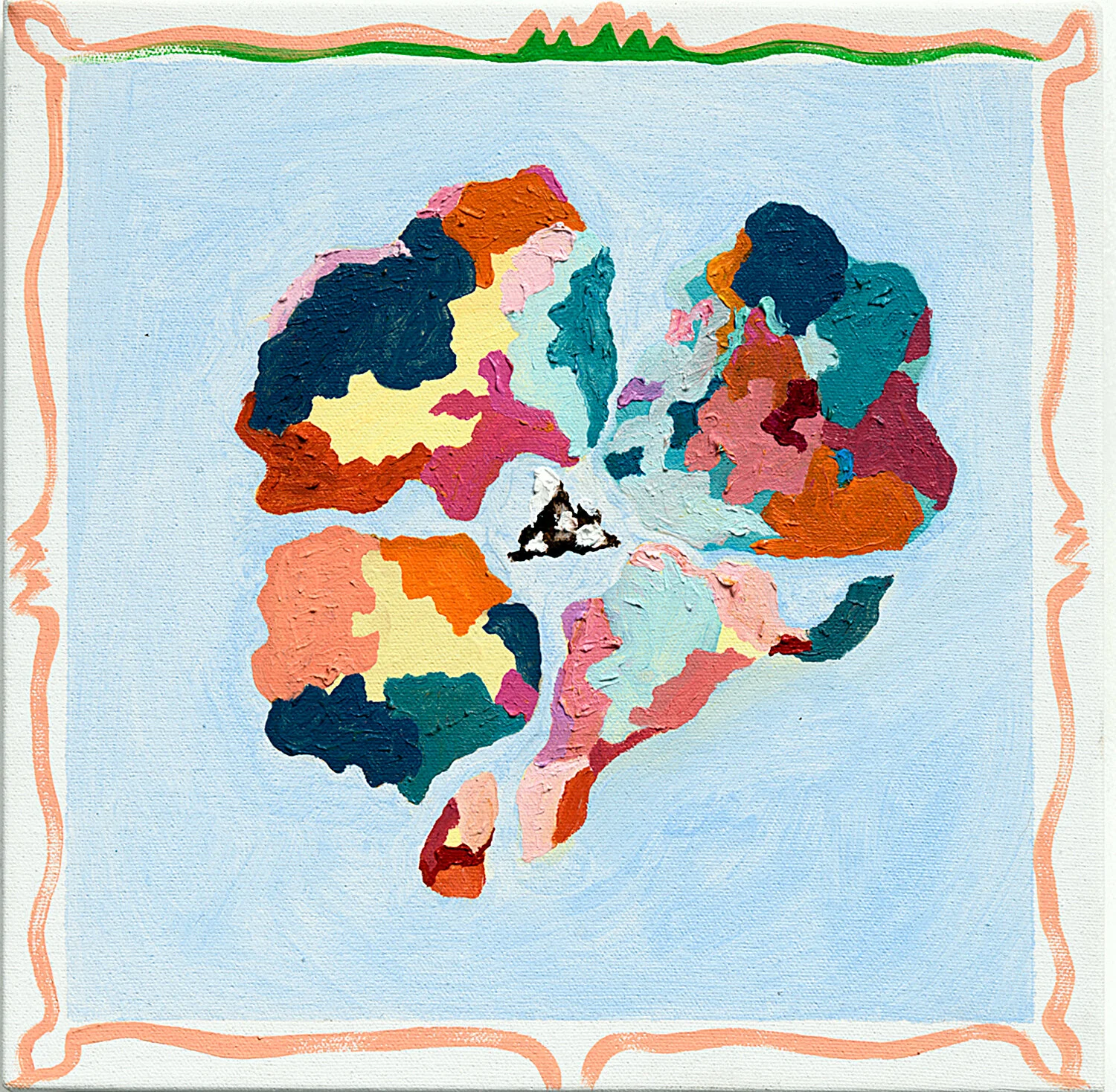

The palette — pale parchment yellow, radiant aquamarine and emerald, fleshy, fruit roses and reds, lovely warm raspberry, and cool olive — is an evocation of Spring with its fecundity and metaphor-friendly stance of hope. The paint is thickly applied, offering topographical and emotional texture and enacting small passages of abstraction within cartographic regulations. The organic contours of geological borders are at odds with the clunky, arbitrary nature of state and national borders, revealing the latter as illusions in the same way as such borders are equally irrelevant to the virus.

The lands, though redolent with flowers both in bloom and in decay, are largely absent of figures. This is both a literal reference to the absence of society during quarantine, as well as the invisible nature of the virus itself. It is also a way of holding space for her abstractionist impulse, creating opportunities for generative, evocative nature to reclaim the planet we are parsing. As we proceed from a recognition of Italy, the United States, Great Britain, the South Pole and so on to an increasingly abstract environment, orientation within the terrestrial field gives way to the more amorphous territory of ourselves. We will have to relearn the world outside when this is over — but it’s the world inside that we are exploring now, and in these paintings being mapped out in all its unknown terror, pleasure and promise.

— Shana Nys Dambrot

Los Angeles, 2020

My Spring Map paintings are inspired by the quarantine of Covid-19. They are a means to juxtapose the 14th century plague with the 21st century pandemic. Using Renaissance maps to speak to the spread of disease felt fitting as a starting point for finding our place in a new unknown world. The geography of these old maps is inaccurate, strange and unsettling. I’m using this inaccuracy deliberately to convey confusion and disorientation.

My Mappa Mundi takes inspiration from Martin Waldseemuller’s 1507 map of the globe (the first map to name “America”). Creating the painting out of twelve canvases (each measure eighteen by twenty four inches), using the identical measurements as the 1507 map, seems the perfect metaphor for how the entire globe has been shattered by Covid-19, nation’s shutting borders and residents under lockdown, all separated.

Covid-19 has been largely an unseen, silent killer, almost an abstraction. Victims have been obscured by medical equipment and by quarantine. The map paintings use paint as an abstraction and nature as our symbol of hope going forward. The use of boundaries is my metaphor for boundaries between the virus and humanity. Each line is deliberately wavy, deliberately handmade as it moves through time and space, my personal framing of the pandemic. The colors are a nod to spring and regeneration, including flowers in states of full blossom as well as decay. The paintings are my thoughts and dreams of our place in time.

— Susan Lizotte